Accessibility and the Shadow DOM

February 05, 2014

A lesson on rendering trees, emerging technologies and tacos. This post was migrated from its original location on the Substantial blog.

tl;dr

Web Components, including Shadow DOM, are accessible because assistive technologies encounter pages as rendered, meaning the entire document is read as “one happy tree”. With a polyfill to add broader support, users with modern browsers can interact with Web Components using a keyboard, touch or mouse. Screen readers will also read the page aloud, illustrating how Shadow DOM fits seamlessly into the regular DOM.

It’s easy: to make Web Components accessible to all users, write accessible code.

Introduction

If you’re like me and you have an interest in cutting-edge technology, you may have heard about the emerging standards capturing the attention of web developers. Web Components are a group of new technologies aimed at encapsulating related styles and scripts together in separate containers to minimize conflicts with the rest of a document, similar to the approach of an iframe. There are multiple parts to the Web Components specification working their way through the W3C and into a few browsers. Official descriptions from the W3C:

- Templates define chunks of markup that are inert but can be activated for use later.

- Decorators apply templates based on CSS selectors to affect rich visual and behavioral changes to documents.

- Custom Elements let authors define their own elements, with new tag names and new script interfaces.

- Shadow DOM encapsulates a DOM subtree for more reliable composition of user interface elements.

- Imports define how templates, decorators and custom elements are packaged and loaded as a resource.

This group of technologies has potential to radically change how web applications are built and bring them more in line with traditional object-oriented software engineering, i.e. modular, encapsulated components with well-defined interfaces.

Given my interest in web accessibility, I was curious how custom Web Components might impact user experience with assistive technologies, in particular screen readers. Because of its effect on the DOM (Document Object Model), the portion of the spec that I wondered about most was Shadow DOM. It was also my first introduction to Web Components.

In this article, I’ll dive in to the accessibility implications of Shadow DOM and shine some light on the current situation.

Why accessibility?

If we’re talking about a new approach to building websites, isn’t it important that everyone can access them? The “accessibility community” has traditionally referred to persons with disabilities, such as blindness or low vision, deafness, hard-of-hearing, motor or cognitive impairments. There is a growing belief, however, that making something accessible means that everyone can use it: your customers, your Mom, even you (in the future).

Enter the Shadow DOM

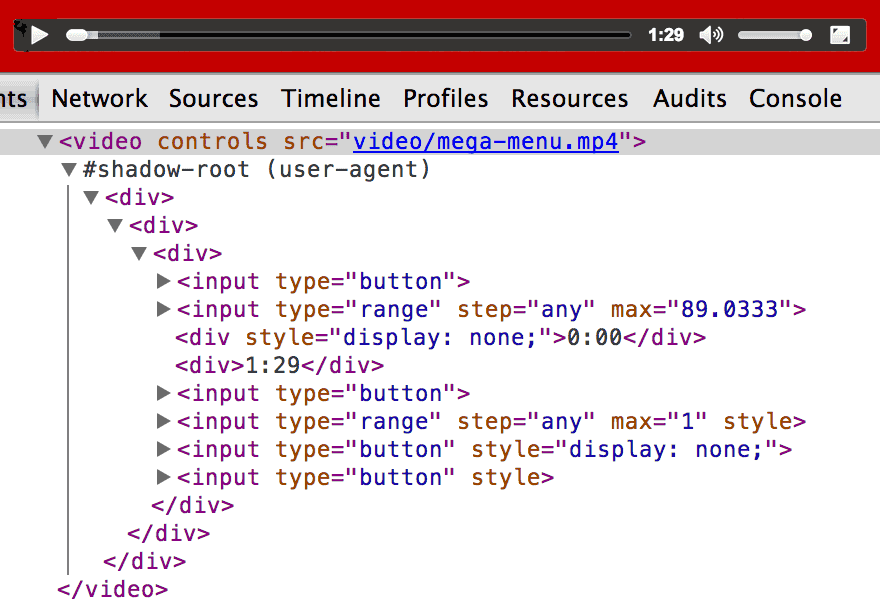

What’s interesting about Shadow DOM in particular is that browser makers have been using it right under our noses for quite some time to style elements without affecting web standards: HTML tags such as textarea, input and the HTML5 video element all contain child elements “hidden” behind a Shadow DOM boundary. We can just now start to see evidence of this technique in the greater web ecosystem when inspecting elements in browsers that support this feature, such as the latest versions of Chrome (after toggling the option in Settings) and Firefox Nightly.

Pictured: HTML5 video tag with “Show Shadow DOM” enabled in Chrome Developer Tools

Pictured: HTML5 video tag with “Show Shadow DOM” enabled in Chrome Developer Tools

How could people use it?

To connect the possibility of using this shiny, obscure technology to real(ish)-world scenarios, there was Polymer, a pre-alpha project by Google, containing polyfills that broadened compatibility of Web Components to “evergreen” browsers: IE10+, Chrome, Firefox, Safari and a couple of mobile browsers (see compatibility matrix).

There wasn’t much in the way of website analytics for screen readers due to privacy concerns and most assistive technology software being system-installed applications. I was able to refer to the WebAIM Screen Reader Survey to assess browser and screen reader preferences as reported by users (there is also a new version coming any day now). In terms of screen readers, JAWS, Window-Eyes and VoiceOver were the most widely used. For browsers, I knew there was a lot of Internet Explorer 8 and below, some Firefox and less Chrome—I’m still curious about what we’ll see in this year’s survey.

Initial thoughts about Shadow DOM access

When I first heard about Shadow DOM, given that I’m not a browser implementer, I had some questions. Would there be any noticeable difference for assistive technology when encountering content in the Shadow DOM versus the regular DOM? Was there anything about the nature of encapsulation that would cause trouble for assistive technologies? An older HTML5Rocks article by Web Components spec editor Dominic Cooney mentioned that “you shouldn’t put content in Shadow DOM” because it would be inaccessible to a screen reader or search engine. Was this true?

In my initial research, I found a Web Components article with a brief mention of accessibility as well as example components that didn’t work with a keyboard. “Uh oh”, I thought…will we be able to navigate the Shadow DOM with keyboards? This article led me to the only post at the time wholly devoted to the topic: Steve Faulkner at the Paciello Group had written about Web Components and ARIA back in 2012. His findings were that “screen readers can access content in Shadow DOM without issue.” This was also confirmed by a short post on the Polymer FAQ:

“A common misconception is that the Shadow DOM doesn’t play nicely with assistive technologies. The reality is that the Shadow DOM can in fact be traversed and any node with Shadow DOM has a shadowRoot property which points to its shadow document. Most assistive technologies hook directly into the browser’s rendering tree, so they just see the fully composed tree.”

How Do Screen Readers Interact With a Browser?

Research into the accessibility of Shadow DOM provided great news for everyone moving forward. Still, I wondered how a screen reader could access content that was supposed to be encapsulated from the rest of a document. I hadn’t previously researched the internals of a browser, so the concept of a DOM tree versus a rendering tree was new to me. I’m still learning how browsers work, but I did find some good information about assistive technology and Shadow DOM.

According to section 7.5 of the Shadow DOM spec:

“User agents with assistive technology traverse the document tree as rendered, and thus enable full use of WAI-ARIA semantics in the shadow trees.”

The “as rendered” part of that statement highlights the fact that screen readers encounter source code after it has been manipulated with JavaScript and CSS, similar to what’s visible in the Chrome or Firefox Developer Tools (as compared to View Source, which is pre-render). That made sense considering screen readers are affected by JavaScript and some CSS properties. When Shadow DOM nodes, or subtrees, are appended to a parent document, they are read aloud as “one happy tree” to a screen reader.

The “as rendered” part of that statement highlights the fact that screen readers encounter source code after it has been manipulated with JavaScript and CSS, similar to what’s visible in the Chrome or Firefox Developer Tools (as compared to View Source, which is pre-render). That made sense considering screen readers are affected by JavaScript and some CSS properties. When Shadow DOM nodes, or subtrees, are appended to a parent document, they are read aloud as “one happy tree” to a screen reader.

Hands-on research

In addition to reading everything I could about Shadow DOM and accessibility, from mailing lists to blog posts, I furthered my research by creating custom components and testing different scenarios.

Keyboards

The first thing I wanted to test was whether the Shadow DOM was navigable by keyboard—I was thrown off the trail by inaccessible widget examples on CSS-Tricks.com—to find out, I created a test page on Github containing a custom drop-down widget and a button that I knew were keyboard-active in the regular DOM and injected them into the page via the Shadow DOM.

After learning a ton about registering elements, creating callbacks, template tags and new CSS properties, I found that the Shadow DOM IS navigable by keyboard. D’oh! Of course it would be, I thought—wouldn’t browser makers have keyboard users’ backs? Not necessarily, as shown by the HTML5 video tag, but in this case, the mouse-enabled controls in the CSS Tricks examples weren’t accessible via the keyboard no matter if they were in the Shadow DOM.

On my test page, the Shadow DOM drop-down and button widgets were fully keyboard accessible and responded to the same input as their regular DOM counterparts. This was great news for keyboard users!

Screen Readers

The next thing I wanted to test was how a screen reader interacted with the Shadow DOM. I got demo copies of JAWS 15 and Window Eyes set up on Virtual Box, in addition to VoiceOver on Mac. Since Polymer only extended compatibility as far back as IE10, I kept my test suite intentionally small, but testing could easily extend to older screen readers and mobile browsers with more time. I added Polymer’s platform.js to shim in basic support for Web Components in browsers besides Chrome, leaving out their larger component library in favor of my own implementation.

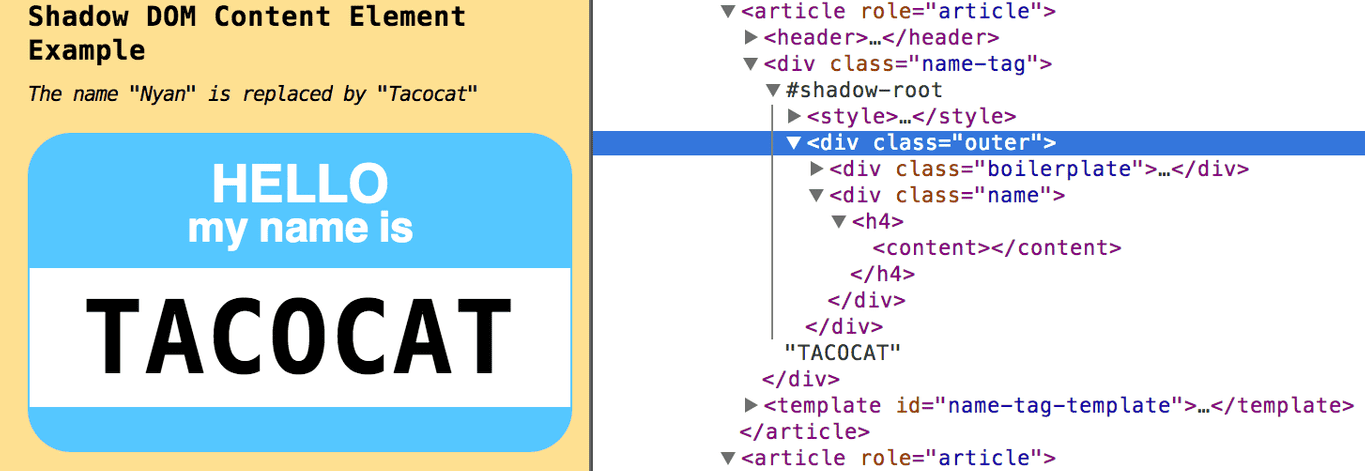

I had seen mentioned in a few places that “content should be kept out of the Shadow DOM” and only “presentation-related divs” should be used. I also heard that people on the Internet really love tacos. So to test the accessibility of Shadow DOM in a screen reader, I created a <taco-article> component containing a heading, link and paragraphs that I knew were accessible in the regular DOM, as well as a button with text replaced by Shadow DOM content to see what was read aloud. Lastly, I emulated a name-tag example in Dominic Cooney’s Shadow DOM article to see if the new <content> tag read correctly.

Pictured: Name tag example shows text rendered in Shadow Root, projected via

Pictured: Name tag example shows text rendered in Shadow Root, projected via <content>. The heading is read as “Tacocat, Heading Level 4.”

In IE10, I wanted to see what happened without compatibility support so I intentionally disabled Polymer. Surprisingly, my drop-down widgets that were included via <template> tags just worked. But they weren’t supposed to—IE hasn’t even hinted at supporting Shadow DOM (other than this post about Canvas). Upon looking in the F12 Developer Tools, I found that instead of throwing an error, the template tag was treated as a regular div and my widget was instantiated in the regular DOM. Oops! I added some CSS to my reset stylesheet to hide the template tag, and then it behaved more like normal: no Shadow DOM widget. So I reenabled Polymer, and voilà! Shadow DOM-enabled elements became visible in IE10.

When I enabled JAWS, I found that every piece of content on the page read correctly, no matter if it was in the regular DOM or the Shadow DOM. JAWS respected heading levels and navigation and had absolutely no trouble reading the entire page. A really interesting example was a name tag with text projected into a <content> placeholder that appears empty in the Developer Tools (see screenshot above). Pre-render, it only contained the word “Nyan”. After being initialized with additional content from a Shadow DOM template, a name tag was rendered. JAWS then read the complete heading: “Tacocat, Heading level 4.” It said the word funny, but it was otherwise accurate!

Window-Eyes in Firefox for PC had some trouble navigating my taco-article at first, but it just seemed buggy—the summary would skip over it, but hovering on it would read all of the content. When I added the same article to the regular DOM for comparison, both versions started being read aloud. I then reverted to just the Shadow DOM taco-article and it started reading correctly in the page summary. Chalking that one up to user error. Window Eyes in Firefox seemed to work just fine.

Lastly, I checked the sandbox in Voiceover for Mac. Besides its inability to correctly say the word taco, I experienced normal behavior when reading headings, links, buttons, interactive widgets and text replaced via the Shadow DOM.

Takeaways

In conducting these experiments, I learned many different things:

- Screen readers encounter one happy, rendered tree when reading a page containing Shadow DOM.

- New standards are developed by people—there are problems and bugs that must be addressed over time, with help from the community. Shadow DOM may have had issues at one time, but implementers have made sure it could be accessed by everyone. The coolest part is that we as developers can participate in the creation of new technologies.

- JAWS and Window Eyes have free demo versions that are perfect for testing.

- The Cat and Hat CSS selectors are not yet supported in SASS.

- Native HTML5 video controls, a Shadow DOM implementation, are only keyboard accessible in Internet Explorer. Who knew?

But, most importantly, I learned that the same accessibility problems exist no matter what kind of DOM you create. Allow users to interact without a mouse and provide readable content that’s more than just visual. For basic accessibility tips, refer to the A11YProject or WebAIM.

Finally, any good project wouldn’t be complete without questions for further research. Among them:

- What about nested Shadow DOMs? Multiple shadows on one shadow host?

- Are there any quirks with tab index on multiple Web Components in a page?

- What are some best practices for styles and scripts when creating Web Components?

- Does Shadow DOM usage have any SEO implications?

- Why aren’t HTML5 video controls keyboard accessible in Chrome or Firefox?

I look forward to answering these questions and seeing new technologies advance their way into our daily projects. I’m very encouraged by the passion my fellow developers have for asking questions and pushing the Web forward. Its future is bright!